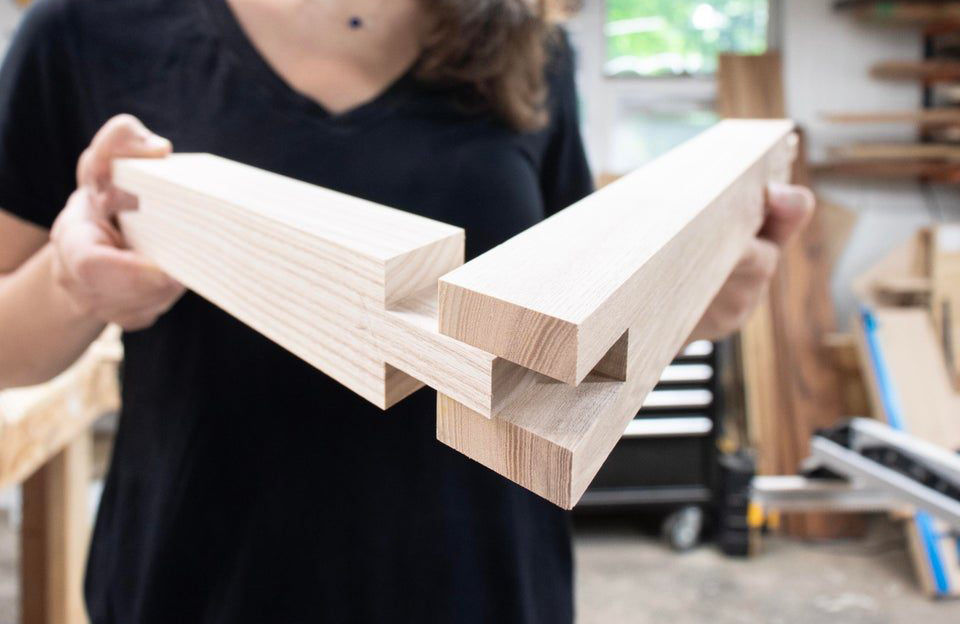

Mortise-and-tenon joint

This is a general term – the mortise describes a pocket cut into a piece of wood, and the tenon is a corresponding positive part on the end of another piece of wood that fits into the mortise.

The tenon shoulders, often cut at square 90-degree angles, seat against the face where the mortise is cut, providing strength and structure while preventing tipping or racking out of square.

There are dozens of variations, and the mortise-and-tenon joint takes many forms. It can be rectangular, square, pinned, wedged, haunched, loose and even cylindrical.

Dovetail joint

Found frequently on drawers, the dovetail is the Holy Grail of woodworking joints. The wedge-shaped pins and tails are cut on mating pieces which resist being pulled apart.

The dovetail is beautiful and strong, but among the most difficult joints to execute. Dovetails can be hand cut, using a combination of careful saw and chisel work, or cut with an array of available router templates, ensuring proper alignment of the pins and tails. In either case, careful layout and patient attention to detail are essential.

While half blind or hidden dovetails do exist, most dovetails are left exposed. That’s because the joint is beautiful and proves the maker is a fastidious craftsperson.

These are the 10 most common woodworking mistakes beginners make.

Box joint

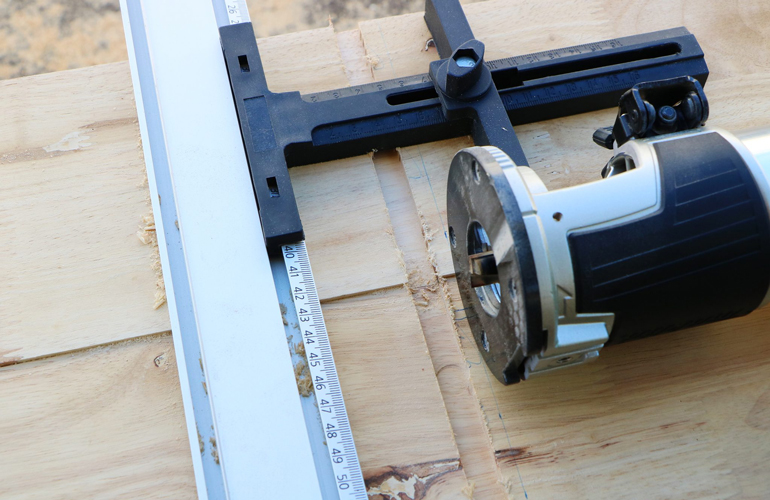

The box joint is considered the fast, strong younger sibling of the dovetail. To picture a box joint, also known as a finger joint, imagine two hands with straight fingers interwoven. While box and dovetail joints can be used interchangeably for the same structural function, the box joint is less extravagant and perhaps easier to execute.

Woodworkers utilise router templates or a stacked dado blade on the table saw to make this clean joint. Once set up, it can be made efficiently.